Across Western democracies, the traditional center-right is collapsing. But there’s one notable exception: Israel.

Why is that the case? And will it remain that way forever? I explored that in my Shabbat column for Yedioth Ahronoth, an excerpt of which is below.

***

A defining global phenomenon of our time is the collapse of the traditional center-right. Across Western democracies, mainstream conservative parties are giving way to more radical, populist movements.

In the United States, Donald Trump absorbed and reshaped the Republican movement, transforming a pro-free-trade party into the isolationist, working-class MAGA movement, complete with protective tariffs. Germany’s far-right is rising at an alarming rate. Chancellor Friedrich Merz, representing Germany’s conservative party, only returned to power after enduring significant parliamentary humiliation.

In the Netherlands, Geert Wilders—a fiercely anti-Islamic, pro-Israel politician—recently brought down the coalition after initially propping it up. As for France, the country’s historic conservative party is now little more than a fading memory, with the Le Pen family dominating right-wing politics for nearly a generation and inching ever closer to the presidency.

But perhaps the most striking story is unfolding in Britain, known historically as a bastion of moderation, and home to the world’s oldest conservative tradition. My recent visit to British Parliament, however, revealed a palpable sense of impending political upheaval.

The Labour Party initially won elections due to widespread fatigue with 14 years of Conservative governance, yet Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s popularity has plummeted, dragging—surprisingly—the main opposition party down with him. Now, polls show Nigel Farage’s anti-immigrant Reform party leading—attracting support from both disillusioned Labour working-class voters, and significant segments of traditional Conservatives. If Farage succeeds, Britain could witness the first victory of a third party in over 110 years.

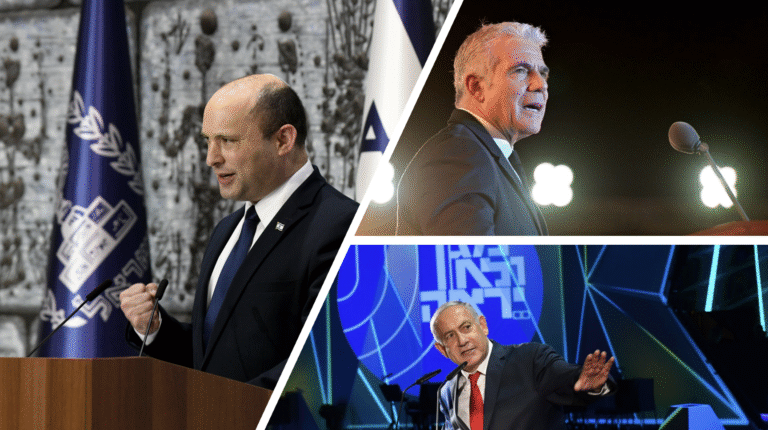

Interestingly, one notable exception to this trend is Israel. Despite being frequently portrayed internationally as a country sliding toward radicalism, Israel’s far-right parties have struggled to achieve lasting dominance. Their peak came in recent elections, securing about ten percent of the vote, but since then they’ve waned: Bezalel Smotrich hovers around the electoral threshold, and Itamar Ben-Gvir fluctuates between six to ten seats.

Why, in a country consistently accused of aggressive nationalism and exposed more intensely to terrorism than any Western nation, isn’t the far-right gaining more traction? The reason, as with many things in Israel, lies largely with Benjamin Netanyahu. As the longest-serving leader in the Western world today, Netanyahu embodies an era of traditional conservatives like John Major, Helmut Kohl, and George H. W. Bush. Israel’s right-wing voters are accustomed to voting for Netanyahu, and don’t see credible alternatives.

Alternatively, it is possible that Netanyahu himself shifted toward the far-right, embracing hardline positions on annexation, anti-establishment rhetoric, and restrictive immigration policies. This allows radical voters to get both mainstream conservatism and populist protest through one leader. If this hypothesis proves correct, the day Netanyahu eventually steps down could usher in election results that even his fiercest critics will regret, prompting them to long for the comparatively moderate and statesmanlike leader of old.